The 350-year-old hack for solving your AI troubles.

Why does every prototype you output just feel like ordering the same sandwich but with different bread?

You're sitting in a coffee shop, laptop open, cursor blinking at you with that familiar mix of possibility and dread. You've got a brief to create something genuinely innovative, but somehow every prototype that emerges feels like a slightly prettier version of something that already exists. Sound familiar?

Well, well, well… It turns out this exact creative dilemma was solved 350 years ago by a rebellious Chinese painter-monk named Shí Tāo. And when you combine his insights with what modern science has discovered about creativity and cognition, it might just revolutionize how you’ll think about AI-assisted design.

The problem with copying the masters.

Let me tell you about Shí Tāo first, because his story is basically the 17th century version of every creative's nightmare. Picture the art world of his time: everyone was obsessing over the "Four Wangs" (yes, that was their collective name), a group of painters who had turned artistic excellence into a paint-by-numbers exercise. They'd study the old masters so religiously that creativity had become glorified draw-by-numbers.

Shí Tāo looked at this situation and basically said, "this is creative death by a thousand brushstrokes."

Instead, he developed a philosophy around something he called the "primal mark" — the idea that your very first creative decision shapes absolutely everything that follows. Not just influences it. Shapes it. Like how the first domino you place determines whether you get a beautiful cascade or a disappointing pile.

Now, before you roll your eyes at ancient philosophical wisdom, check this: in 2014, a researcher named Justin Berg at Wharton School of Business decided to test Shí Tāo's intuition with actual experiments. What he found was so interesting that it completely changes how we need to think about the creative process.

Science meets centuries-old wisdom.

Across four different experiments, Berg gave ~800 participants different starting points for creative tasks and then measured what happened to the novelty and usefulness of their final ideas. He wasn't just testing whether starting points mattered — he was testing whether different types of starting points led to predictably different outcomes.

The results were crystal clear. People who started with familiar concepts created things that were practical but predictable. Think of it like following a well-worn hiking trail — you'll definitely reach a destination, but you won't discover anything new along the way.

People who started with completely novel concepts created things that were innovative but often useless. Picture someone blazing through dense forest without a compass — they might stumble onto something amazing, but they're more likely to end up lost in the wilderness.

But people who started with what Berg called "integrative" concepts — mixing familiar and novel elements — created ideas that were both breakthrough and practical. They found the sweet spot where innovation meets utility.

The implications were pretty astounding. Your first creative decision doesn't just matter. According to Berg's data, it's probably the most important decision you'll make in the entire process. Once you commit to developing an idea from a particular starting point, "the fate of any ideas that grow from it may be largely sealed."

You can’t innovate your way out of a bad idea.

Think about that for a moment. We spend enormous amounts of time agonizing over final details, but barely any time thinking about our starting point. It's like obsessing over the perfect steering wheel while letting someone else choose which road you're driving on.

Your brain is basically an AI that never stops.

But there's another piece to this puzzle that makes everything click into place. It’s a psychological concept called "nexting”. You might also know this as “system one” as its often referred to in a broader sense.

Nexting is what your brain is doing right now as you read this sentence. It's constantly, automatically, unconsciously predicting what comes next. Not just in language, but in everything. Where your foot will land on the next step. Where that frisbee will be when you catch it. What word will follow "It was a dark and stormy..."

Your brain constantly predicts the next word while reading, using context clues to maintain fluency. You're thinking about something else entirely right now, yet your neural circuits are busy forecasting what comes next. When predictions fail spectacularly, you suddenly feel happy.

Feel that little jolt of surprise? That's your nexting system getting caught red-handed. You were expecting something like "confused" or "surprised," and when you got "happy" instead, your prediction engine hiccupped and sent you into “system two” — the one that consciously and slowly processes what’s really going on.

Your brain does this game of nexting hundreds of times per second, completely outside your awareness. It's why you can walk without thinking about each step, catch a ball without calculating physics on a piece of paper first, and read without sounding out every letter.

And guess what? This is exactly what large language models (LLMs) do. They're nexting machines, trained on massive datasets to predict what token comes next in a sequence. When you ask Figma Make to design something, it's essentially doing super-sophisticated nexting based on all the designs it's seen before.

The AI orthodoxy trap, explained.

And all of this brings us to our current moment, where AI has become the new "orthodox school" of creative work. And now you can see exactly why this creates the same problem Shí Tāo identified centuries ago.

When you open Figma Make, or Cursor, or whatever your creative poison is, and type "Create a dashboard for travel management," you're essentially asking a nexting machine to predict what should come after those words based on every travel management dashboard that ever existed in its training data. What you get back is the design equivalent of those Four Wangs paintings — technically competent, immediately recognizable, and spiritually completely empty. Bah!

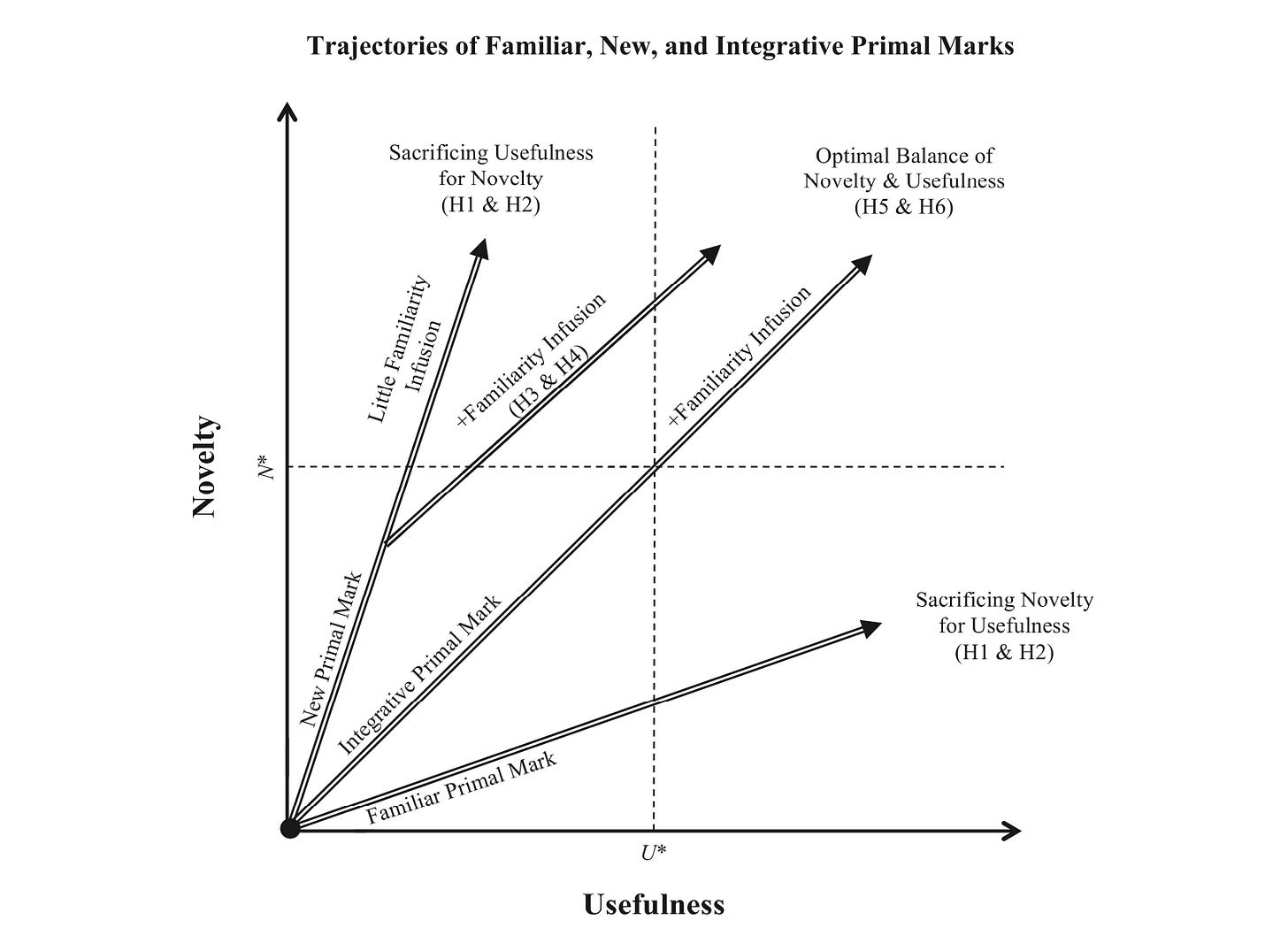

Berg's research helps us understand exactly what's happening. You've set a "familiar primal mark" — one derived mainly from ideas that are already well known and conventional within your domain. According to his experiments, this anchors your trajectory toward usefulness at the expense of novelty. You'll get something that works, but you won't get anything that breaks new ground.

The AI isn't being lazy or uncreative. It's doing exactly what it was designed to do: next its way through the most probable sequence of design decisions based on patterns it learned from existing work. You've accidentally asked it to give you the statistical average of all travel management dashboards, dressed up in slightly different visual clothing.

But what makes this even more insidious is that your own brain is also nexting when you work with AI. You see the first few outputs — boop! — your prediction engine kicks in, and suddenly you're collaboratively nexting your way toward the most probable design solution. You've created what we could recognize as a nexting feedback loop, where human and artificial prediction engines reinforce each other's tendencies toward familiar primal marks.

No wonder everything feels derivative.

The anchoring effect that seals your fate.

Berg's research revealed something crucial about how primal marks work. They don't just influence your creative process — they anchor it. Drawing from psychological research on anchoring effects in numerical tasks, Berg showed that "the initial content in the primal mark may impact novelty and usefulness disproportionately more than content added later in creative tasks."

Think of it like this: if you start building a house on swampy ground, no amount of beautiful architecture can save you from the fundamental instability of your foundation. Similarly, if you start with a familiar primal mark, "employees may be primed to have familiar schemas dominate their thinking as they develop their ideas, diminishing the ease with which any relatively novel elements or associations may come to mind."

This is why those iterative AI sessions often feel so frustrating. You keep polishing and refining, but somehow you never escape the gravitational pull of that first conventional idea. Berg's experiments showed that novelty is "more rigidly anchored by the primal mark than usefulness." Once you commit to a familiar starting point, you've essentially placed a ceiling on how innovative your final result can be.

Shí Tāo understood this intuitively when he wrote about painters becoming "beclouded by things" and "engaged with a thing's dust." In our case, that dust is the accumulated sediment of every interface that ever existed, now crystallized in the AI's training weights and reinforced by our own nexting tendencies.

The method of no-method for breaking the nexting trap.

So what's the solution? Berg's research points toward what he called "integrative primal marks" — starting points that combine familiar and new content. These require what he describes as "analogical thinking," which helps people identify novel connections between previously distinct ideas.

Shí Tāo called this the "method of no-method." Which sounds like philosophical wordplay until you realize it's actually the most practical creative advice ever given for our current situation. The method of no-method means being free from dependence on predictive patterns. It means recognizing when you're nexting and consciously choosing to break the chain.

Applied to AI, this changes everything. Instead of asking the AI to next its way through a familiar problem, you ask it to help you explore genuinely uncharted territory.

Instead of "Create a dashboard for travel management," what if you started with something like this:

"Explore how ancient migration patterns and wayfinding rituals could inform how modern travelers navigate their journeys. Consider both the intuitive connection nomads had with landscapes and the overwhelming data streams of contemporary travel. What emerges when we honor both the human need for discovery and the practical reality of complex logistics?"

Suddenly you're not asking the AI to predict the next most likely interface. You're asking it to help you imagine something that doesn't exist in its training data. You're forcing it out of nexting mode and into something closer to genuine synthesis. You're creating what Berg would recognize as an integrative primal mark.

The surprising power of integrative starting points.

Berg's experiments revealed something remarkable about integrative primal marks. Not only did they produce ideas that were more novel than familiar starting points and more useful than purely new starting points — they actually optimized for both dimensions simultaneously.

This happens because integrative primal marks require you to engage in what Berg calls "analogical thinking" right from the start. When you try to combine familiar and new elements, "individuals search for higher-level, abstract parallels between two or more ideas, as opposed to similarities between the lower-level literal attributes of the ideas."

This complex thinking "may foster the identification of more fundamental — and thus more novel — ways of recombining the familiar and new content into one emerging idea." At the same time, because integrative primal marks include familiar elements, you can "leverage these familiar schemas to enhance the clarity, meaning, legitimacy — and thus usefulness — of their emerging ideas."

It's like having the best of both worlds. You get the innovation that comes from genuine novelty, plus the practical grounding that comes from familiar patterns. The familiar elements help others understand and appreciate the novel aspects, while the novel elements prevent the familiar from becoming stale.

AI as a brush and ink, not a fortune teller.

But there's a distinction we need to make about how we use AI in this process.

"The painter moves the ink, the ink does not move the painter."

— Shí Tāo

In other words, mastery means maintaining creative agency while using tools, not becoming a servant to your tools' capabilities.

This insight becomes critical when we understand that AI is essentially a sophisticated nexting machine. These tools generate results so quickly and confidently that it's easy to slip into a mode where you're crowd-sourcing your creative decisions to statistical patterns.

I see this happening everywhere. Designers using AI-generated wireframes as starting points and then just polishing them. Writers using AI drafts as foundations and then just editing them. Strategists using AI frameworks as templates and then just customizing them.

The problem isn't that these approaches are wrong. The problem is that they're limiting. You're letting the AI's nexting become your primal mark, which means you're anchored to its statistical understanding of the problem, not your human understanding of what's actually needed.

Berg's research suggests a different approach. Use AI as raw material for creating integrative primal marks, not as a source of familiar starting points. Let it help you explore the unexpected combinations and analogical connections that neither of you would reach alone.

The three stages of enlightened AI creativity.

Using Shí Tāo's philosophy, Berg's research, and our insights about nexting, here’s my three-stage approach to unlock genuinely breakthrough work:

Stage one: Breaking the nexting chain.

Before you touch any AI tool, consciously interrupt your brain's automatic nexting. Don't immediately jump to "what should the solution look like?" Instead, ask yourself: What assumptions am I bringing? What would the most obvious nexting path produce? What human need exists beneath the surface requirements that might lead to a completely different starting point?

This isn't meditation (though it could be). It's strategic thinking about your primal mark before you commit to one. Because once you start nexting — whether human or artificial — you're on a path that Berg's research suggests is very hard to escape.

Stage two: Integrative prompting that breaks AI nexting.

When you do engage AI, craft prompts that force it out of its natural nexting patterns. Combine domain-specific needs with completely unexpected perspectives. Ask it to explore contradictions, not resolve them. Use it to question the problem definition, not just solve the problem as stated.

The goal is to create integrative primal marks that blend genuine human insight with novel approaches that exist outside the AI's most probable prediction chains. You want to start with something that makes you slightly uncomfortable — a sign that you've successfully avoided familiar territory.

Stage three: Conscious nexting detection.

As you iterate, stay vigilant for moments when you slip back into collaborative nexting with the AI. When outputs start feeling familiar or "right" in an obvious way, that's often a sign that you've fallen back into pattern matching rather than genuine exploration.

Berg's research suggests that "usefulness is more flexible than novelty" — you can make a novel idea more useful later, but you can't easily make a familiar idea more innovative. So when in doubt, err on the side of strangeness. Use surprise as your compass.

The real revolution: AI as mirror for creative consciousness.

There's another interesting opportunity hiding in plain sight. When you understand that AI is essentially a nexting machine trained on human cultural output, you start to see it as something unprecedented: a mirror that reflects back the collective creative patterns of our entire civilization.

When AI generates something predictable, it might be showing you the statistical average of human creativity in that domain. When it generates something unexpected, it might be revealing combinations that exist in the data but that we've never consciously noticed.

Berg's research showed that people naturally gravitate toward familiar primal marks about 60-80% of the time. We have a cognitive bias toward the safe and conventional. AI can help us see this bias in action and deliberately work against it.

With AI, we have the opportunity to partner with the collective intelligence embedded in human culture while maintaining our unique capacity for genuine imagination — what we can distinguish from nexting as our ability to envision truly distant, hypothetical futures.

What this means for your next project.

So the next time you're starting a new project, pause before opening your AI tool of choice. Ask yourself: Am I about to set a primal mark that leads to predictable nexting? Or am I creating space for something genuinely new to emerge?

Remember Berg's finding that your first creative decision may seal the fate of everything that follows. Both you and the AI are nexting machines, but the creative opportunity lies in consciously breaking those nexting chains and using the AI's pattern-matching capabilities to explore territory that neither of you would reach alone.

Watch for the moment when outputs start feeling "right" too quickly. That's often a sign that you've fallen into what Berg identified as the familiar primal mark trap. The magic happens when you stay in the productive discomfort of not knowing exactly where you're going.

And when you do hit something genuinely novel, pay attention to how it happened. You'll often find that breakthrough moments occur when you've successfully created what Berg would recognize as an integrative primal mark — a starting point that honors both human need and genuine possibility.

After all, we're not just making products. We're participating in the ongoing creation of culture. The question is: Do you want to help that culture next its way toward more of the same? Or do you want to help it imagine something it's never seen before?

Your first creative decision probably determines which one you get.