The execution trap: how change turns strategic leaders into sprint zombies.

Teams don't freeze when uncertainty hits. They sprint faster. Here's how design leaders can escape the busywork trance and provide direction even when strategy is unclear.

I've watched brilliant design leaders turn into micromanaging sprint zombies overnight. One day they're setting bold product vision, the next they're obsessing over whether the loading animation should be 200ms or 300ms.

What happened?

Change hit. And instead of rising to meet it, they retreated into the false comfort of execution busywork.

The great narrowing.

Your Slack is pinging. Another "urgent" request. Your team is three sprints deep into a redesign project, but you can't shake the feeling that everyone is running hard in different directions.

Here's what they don't tell you about organizational change: teams don't freeze when uncertainty hits. They sprint faster. Much faster.

When change slams into an organization (reorg, leadership turnover, market disruption) something predictable and dangerous happens. Teams retreat into what feels safest: immediate deliverables. Engineering obsesses over sprint velocity. Design disappears into pixel-perfect mockups. Product becomes a feature factory.

Everyone stays busy. Everyone ships something. But step back and you'll see the brutal truth: the work keeps happening, but no one knows where it's leading.

This is the execution trap. That false comfort of "at least we're shipping something" that kicks in when the bigger picture becomes unclear. It's a psychological defense mechanism that feels rational but creates organizational drift.

"Change and uncertainty are part of life. Our job is not to resist them but to build the capability to recover when unexpected events occur." — Ed Catmull

The reality is that most leaders respond to ambiguity by doubling down on what they can control. And the leaders who retreat into execution busywork during change (micromanaging deliverables instead of providing direction) are often the same ones who were strategic thinkers during stable times.

Change doesn't kill strategy. It reveals which leaders know how to operate at the tactical level where they can provide direction even when the bigger picture is unclear.

The execution trance.

Picture the frazzled leader's weekly routine during organizational change: Sprint planning Monday. Design reviews Tuesday. Stand-ups every morning. Progress reports every Friday. An endless cycle of "this sprint, next sprint" that creates the illusion of progress while teams slowly drift apart.

This is the execution trance. A hypnotic focus on immediate deliverables that feels productive but lacks coherent direction. When the strategic sky is cloudy, it's natural to look down at your feet. The problem is, when everyone's looking down, no one's navigating.

Research from teams in extreme environments reveals something crucial: under stress, we experience what psychologists call "cognitive narrowing" (a diminished understanding of the situation). Your design team isn't choosing to ignore the bigger picture. They're experiencing a psychological response to uncertainty that makes tactical thinking nearly impossible.

The symptoms are everywhere:

Teams optimize for activity over outcome. Velocity becomes the north star. "We completed 15 story points this sprint" matters more than "We moved the needle on user retention." The rituals become the purpose. It's corporate theater disguised as productivity.

Leaders retreat into micromanagement. Without clear strategic direction to provide, leaders focus on what they can control: process, deadlines, deliverable quality. It's easier to debate whether a button should be blue or green than ask whether the button serves the right user need.

"Immediate value" becomes the rallying cry. Teams justify every decision by showing short-term impact, even when those impacts don't add up to anything meaningful. It's organizational click-bait optimization.

"Good strategy requires leaders who are willing and able to say no to a wide variety of actions and interests. Strategy is at least as much about what an organization does not do as it is about what it does." — Richard Rumelt

Everyone's moving, sprinting even, but nobody knows where they're going. They're sprint zombies.

The three levels of leadership vision.

To understand why teams default to execution during change, you need to map the three levels where leaders operate. Think of it as altitude training for leadership:

Ground Level (Execution): The 50-foot view

Your daily grind. Sprint planning, task management, immediate problem-solving. Time horizon: days to weeks. The trap? Tactical myopia (executing blindly without questioning strategic fit).

Eye Level (Tactical): The 5,000-foot view

This is where the magic happens. You're connecting sprint work to broader themes, translating fuzzy strategy into coordinated action. Time horizon: weeks to quarters. The trap? Getting stuck in process optimization instead of providing direction.

Sky Level (Strategic): The 50,000-foot view

The big picture. Market position, long-term vision, resource allocation. Time horizon: quarters to years. The trap? Becoming so abstract you lose touch with execution reality.

During organizational change, the strategic level often becomes foggy. The destination isn't clear. When this happens, ground-level teams feel lost. They can't see the bigger picture, so they focus on what they can control: their immediate tasks.

This is where tactical leadership becomes absolutely indispensable. Leaders operating at eye level can provide direction even when the strategic picture is unclear. But most leaders get this completely wrong.

The tactical sweet spot.

While strategic leaders set the destination and execution leaders handle the journey details, tactical leaders do something different: they provide direction when you don't have perfect clarity about the destination.

Think tactical leadership like GPS recalculating your route. The destination might be the same, but traffic conditions changed. A tactical leader doesn't wait for perfect information about the best possible route. They provide the next best direction based on current conditions.

What tactical leadership actually looks like.

"I'm not sure about our long-term strategy, but here's our approach for the next quarter." A tactical leader might tell their team: "While the company figures out our AI strategy, we're focusing on improving data quality in our existing features. This positions us well regardless of direction."

Instead of saying "ship feature X," tactical leaders explain: "We're shipping feature X because we're testing our hypothesis that better onboarding drives retention. Even if product strategy shifts, understanding what makes users stick will be valuable."

"Never tell people how to do things. Tell them what to do, and they will surprise you with their ingenuity." — George S. Patton

Tactical leaders operate in what’s called proximate objectives (clear, achievable near-term goals everyone can rally around when distant goals are hard to grasp). They pattern-match across recent work, spot emerging themes, help teams see how individual contributions connect to something bigger.

The secret isn't having all the answers. It's what Netflix's culture calls "lead with context, not control." Share the relevant information (the why, goals, constraints) then step back and let people make decisions within those guardrails.

Building psychological safety for tactical thinking.

Perhaps most crucially, tactical leaders create psychological safety — an environment where people feel secure enough to voice concerns, suggest ideas, learn from failures. During ambiguous times, this becomes vital.

"Psychological safety is not about being nice or lowering performance standards. It's about giving candid feedback, openly admitting mistakes, and learning from them." — Amy Edmondson

Without this foundation, teams retreat further into execution mode rather than engage in collaborative problem-solving that uncertainty demands. But when people feel safe to say "I think we're going in the wrong direction," tactical leaders harness collective intelligence to navigate ambiguity.

As Simon Sinek puts it: "A team is not a group of people that work together. A team is a group of people that trust each other." During change, trust prevents teams from fragmenting into siloed execution units.

Raising the line of sight.

The most valuable skill for leaders during organizational change isn't strategic planning or execution management. It's helping teams raise their line of sight from ground level to eye level.

Most teams naturally operate at ground level during stable times. "What are we building this sprint?" becomes the dominant question. During change, this narrow focus becomes problematic because ground-level work easily disconnects from any larger purpose.

Tactical leaders help teams lift their heads by introducing a new question: "How does this sprint ladder up to something bigger?"

This isn't about demanding perfect strategic alignment. It's about helping teams see patterns and connections. When teams can't see the forest for the trees, tactical leaders help them spot the clearings.

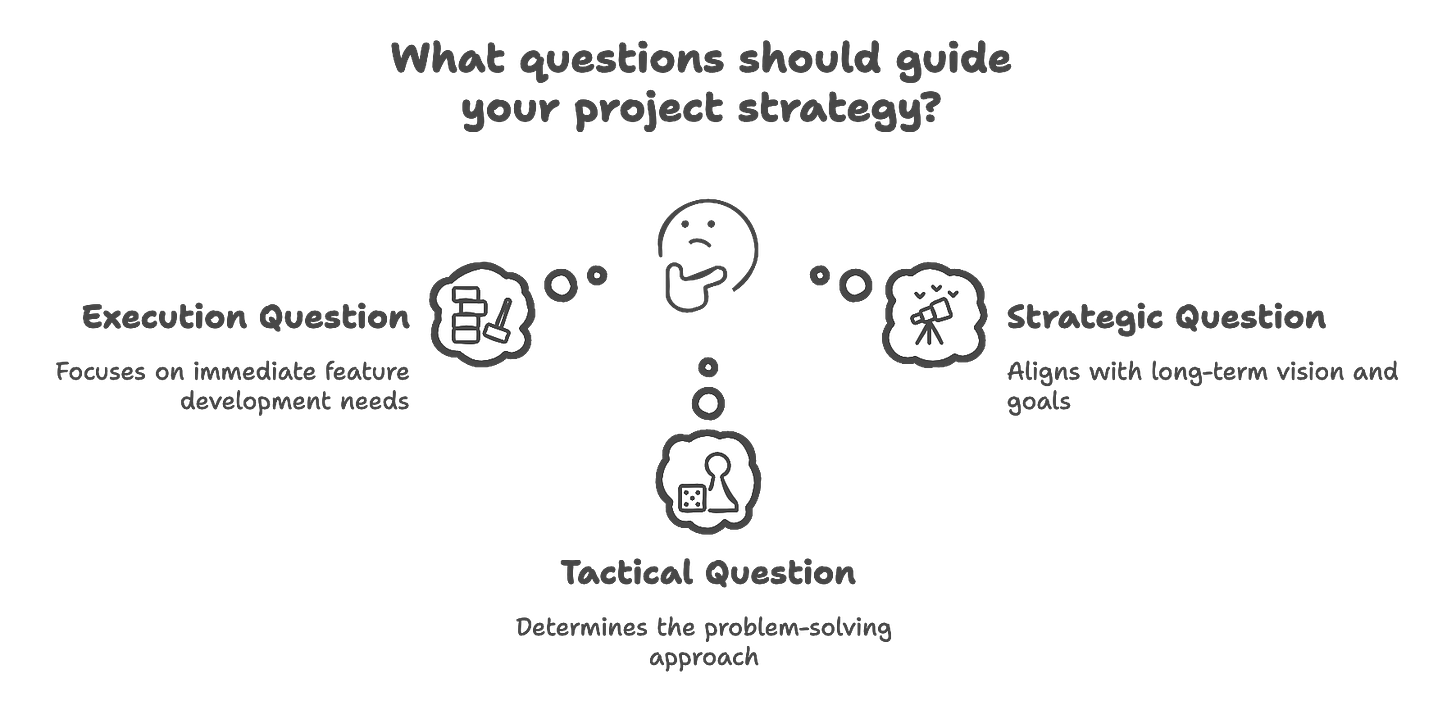

The approach framework.

Tactical leaders help teams think at three levels simultaneously:

Execution Question: "What features do we need to build?"

Tactical Question: "What's our approach to solving this problem?"

Strategic Question: "Where does this fit in our long-term vision?"

The magic happens in the middle question. Even when strategic vision is unclear, teams can usually articulate their approach to solving immediate problems. This approach-level thinking creates coherence without requiring perfect strategic clarity.

Example transformation:

Execution focus: "We're rebuilding the seat selection interface"

Tactical focus: "We're taking an approach that reduces anxiety during booking by showing real-time seat availability and explaining fees upfront, rather than optimizing for upsell conversion"

Strategic connection: "This supports our broader shift toward transparent, customer-first experiences, even though we're still defining what 'premium service' means in our new strategy”

Notice what happened? The team went from a narrow feature focus to understanding their guiding philosophy (reduce anxiety, increase transparency) which helps them make dozens of micro-decisions without constantly escalating to leadership. They know their approach even when company strategy is still evolving.

This pattern recognition separates tactical leaders from execution managers. They're constantly scanning for what's working, what isn't, and what it means for the team's approach.

"If there is more truth in the hallways than in meetings, you have a problem." — Ed Catmull

Building tactical muscle.

Look, tactical leadership isn't some mystical gift you're born with. It's more like learning to drive stick shift. Awkward at first, but once you get the hang of it, you wonder how you ever managed without that level of control.

The best tactical leaders I know have developed what I call pattern radar. They're constantly scanning their teams' work for connections that others miss. While everyone else is heads-down in their individual lanes, these leaders are spotting the threads that weave everything together.

Create space for the "so what?" conversations. The magic happens when someone says, "I notice we keep solving user problems the same way across three different features. What does that tell us?" These moments don't happen accidentally. You have to make room for them.

I learned this from watching a fellow design leader. Every month, she'd gather her team for what she called connect the dots sessions. No agenda, no deliverables. Just: "What story is our work telling?" Teams started seeing patterns they'd completely missed when they were stuck in sprint tunnel vision.

Focus on the connections, not the chaos. Start asking different questions in your existing meetings. Instead of "What did you ship this week?" try "What are you learning about our approach?" Instead of "Are we hitting our velocity targets?" ask "What patterns are emerging across our work?"

You'll be amazed how quickly this shifts the conversation from status reporting to actual thinking.

Teach your team to think like editors, not just executors. Good editors don't just fix typos. They see how individual paragraphs serve the larger narrative. Same with tactical thinking. Help your team members understand how their specific work fits into bigger themes.

The airline example I mentioned earlier? That team learned to ask "Does this reduce anxiety or create it?" about every design decision. That simple filter helped them make hundreds of micro-choices without escalating everything to leadership.

Embrace the experimental mindset. As Eric Ries puts it: "The only way to win is to learn faster than anyone else." Frame your work as experiments that inform strategy rather than features that execute it. When half your ideas don't work (and Marty Cagan reminds us that's exactly what will happen), you're learning, not failing.

The tactical leaders who thrive during uncertainty share one trait: they're comfortable operating in the space between "we know exactly where we're going" and "we have no clue what we're doing." They provide direction without pretending to have perfect clarity.

Most leaders think they need to choose between being strategic visionaries or execution machines. But the real leverage is in the middle. You become the translator between fuzzy strategy and concrete action. You're the one who can say, "I'm not sure about our five-year plan, but I know our approach for the next quarter."

Teams that develop this tactical muscle become remarkably resilient. They can navigate ambiguity because they've learned to see connections, spot patterns, and adjust their approach based on what they're learning. They don't need perfect strategy to make good decisions.

Stop waiting for strategy to get clearer. Start building the muscle that lets you provide direction even when the destination is still coming into focus.